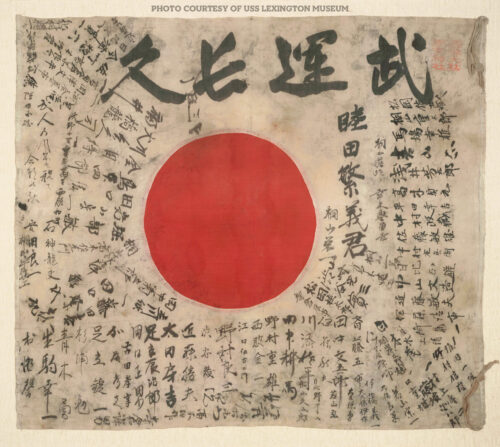

A poignant moment unfolded on Jul. 20 as the USS Lexington Museum in Texas handed over a historical artifact—a Good Luck Flag—belonging to a Japanese soldier who lost his life during World War II. The flag, covered with signatures of Shigeyoshi Mutsuda, his family, and friends, was on display at the Corpus Christi museum for 29 years before being entrusted to the Obon Society, a nonprofit organization that specializes in returning similar flags, considered non-biological human remains, to the families of fallen Japanese service members.

Rex Ziak, co-founder of the Obon Society, acknowledged the profound significance of this return to Mutsuda’s family, equating it to the emotions experienced by Americans when they receive the remains of their own fallen soldiers identified and repatriated after many years. The Good Luck Flag serves as a cherished relic, representing all that remains of a soldier whose body was never recovered.

Hirofumi Murabayashi, consul general of Japan in Houston, expressed gratitude to the USS Lexington Museum for willingly transferring the flag. He emphasized that the gesture exemplifies the enduring friendship between the United States and Japan.

Mutsuda’s fate during the war remained tragic, with his body never found. His wife, who recently passed away at the age of 102, had always hoped for the flag’s return, and her funeral has been delayed until this long-awaited moment arrives.

The Yosegaki Hinomaru, as the flag is known in Japan, had been proudly exhibited on a World War II aircraft carrier at the museum since its donation in 1994. Steve Banta, the museum’s director, described the donation process as routine. Unfortunately, due to record-keeping issues at the time of its donation, the original donor’s identity has remained elusive.

The momentous discovery of Mutsuda’s signature on the flag occurred when one of his sons, now 82, recognized it while viewing an image of the flag. Upon closer examination, he also identified the signatures of other family members, friends, and neighbors, confirming that the flag had indeed belonged to his father. The signatures matched those seen in an old family photo where Mutsuda proudly held the flag, surrounded by loved ones, just before departing for war.

The exact circumstances surrounding the discovery of the flag are not entirely clear. Ziak suggests that soldiers often scoured battlefields for sensitive information, such as maps, and sometimes encountered flags and other items, which they would collect as souvenirs. The Good Luck Flags, easily rolled and carried, became common keepsakes for service members, and thousands were brought home from overseas as mementos.

However, as time passed, the stories of how and where such items were found were lost to history. Veterans would often store them away until their passing, and these significant pieces of the past would only resurface later, holding great importance for their families.

In a poignant conclusion to this chapter of history, the Good Luck Flag will be returned to Mutsuda’s two sons and daughter in Tokyo later this month during a heartfelt ceremony at a shrine honoring Japanese war dead. The artifact’s journey back to its rightful place with the soldier’s family symbolizes the enduring bond between nations and the respect shown to those who made the ultimate sacrifice in service to their country.

For more information, hit the Source below