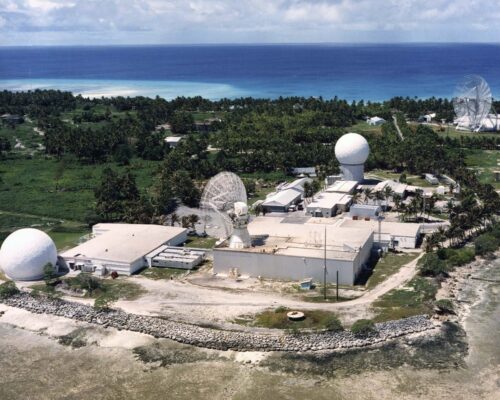

The scene was something out of a disaster movie: doors knocked off their hinges, furniture overturned, and bookshelves toppled, leaving a mess of debris and a lingering question: Is this the future? This was January 2024 on Roi-Namur, the second-largest island in the Kwajalein Atoll, a remote chain of islands in the Pacific Ocean, about 1,100 kilometers north of the equator. According to a report by Aerospace America, this island, home to around 120 US military personnel and contractors, is crucial for operating rocket launch pads, radars, and telescopes, and it forms a key part of the Ronald Reagan Ballistic Missile Defence Test Site. But this vital location is now facing a very real threat from the rising seas of climate change.

Known simply as “Kwaj” to those in the military, the atoll and surrounding test range are a focal point for US missile defence testing, as well as the surge in hypersonic weapon experiments that the US has undertaken to catch up with China. The atoll’s wide open space allows the US to conduct tests without risking damage to property, infrastructure, or people. Its location near the equator also places its telescopes and radars in the best position to track satellites orbiting in the geo-belt. The Millimeter Wave Radar on Roi-Namur, described as one of the finest-resolution imaging radars in the world, is particularly important for identifying space objects. The atoll is also uniquely positioned to provide an early view of Chinese missile and weapon tests over the Pacific. Throughout its history, Kwajalein has hosted key tests and launches, including the first ICBM interception, the first US anti-satellite capability test, and the first ‘hit-to-kill’ interception. It is a key location for modern anti-missile defence technology and US progress on hypersonic weapons.

However, this crucial location is also extremely isolated, sitting some 7,000 km from Australia and 8,000 km from the continental US. As Army Col. Andrew Morgan, commander of the U.S. Army Garrison-Kwajalein Atoll, notes, “This is like the space station. It’s remote and isolated, and resupply is not frequent and not assured”. The flooding on Roi-Namur underscored a grim reality: for low-lying areas like Kwajalein, these kinds of events are going to become more frequent, as rising sea levels caused by climate change pose a significant risk to operations. Roi-Namur has an average elevation of just 2 metres, and the highest point is the 17.5 metre tall artificial hill known as Mount Olympus. The flooding of Roi-Namur in January 2024 saw seawater pour through living quarters, rendering air conditioning units useless, disrupting power, and damaging the dining facility. This forced the evacuation of 80 of the 120 personnel on the island. The flooding was caused by a cyclone that formed near Japan, which created swells that became 4.5-metre waves that crashed into the island.

According to coastal scientist Curt Storlazzi, the seas around the atoll rose 11 centimetres between 1990 and 2020. The United Nations’ World Meteorological Organization has predicted up to 20 cm of additional sea level rise by 2050. Storlazzi notes that this rise means that smaller waves can now travel further inland. A 2018 study also predicted that seawater would intrude into Kwaj’s groundwater, making it undrinkable by 2035. The approximately 1,400 people living on Roi-Namur and Kwajalein Island consume 20 million litres of water a month. The long term impact is even more concerning, with projections indicating that operations on the atoll will become impossible in 85 years due to regular flooding. Additionally, warmer waters will cause more coral bleaching, which leads to smoother reefs that increase flooding.

In response to the challenges, the Army initiated “Operation Roi Recovery”. Water reclamation, particularly atmospheric water extraction, is being considered as a solution to the potable water crisis. DARPA is funding research to develop low-powered water extraction systems for the atoll. As Col. Morgan states, Kwajalein is “an ideal place to demonstrate climate resilience”. There are plans to explore new paints and coatings to protect against the highly corrosive sea spray. The possibility of modernising the radars, replacing analogue with digital components, is also under consideration to reduce the need to maintain climate-controlled storage for spare parts. There are also ideas to rebuild structures away from the most flood-prone areas, raising them above projected sea levels.

The Army’s fiscal 2025 budget includes a proposed $2.2 billion to operate the site, with at least $1.2 million earmarked for research on mitigating climate risk. Despite these efforts, the impact of the flooding has been significant. The focus has been on restoring vital infrastructure, like living quarters, dining facilities and radar systems, which has meant other facilities, such as the chapel and outdoor theatre, have not been rebuilt. As Col Morgan notes “it’s going to be a long time before we ever get back to even where we were, let alone better than where we were”.

Despite the challenges, Col. Morgan remains optimistic, stating, “Kwajalein’s best days are still ahead of us”. He emphasizes that leaders recognise Kwajalein’s importance and are committed to reinvesting in it. He noted that Kwajalein is more important now than it has been in many decades, and needs help to achieve its full potential over the next decade or two. This remote atoll, vital for U.S. missile defence, is battling not just its isolation but also the rising tide of climate change.

For more information, hit the Source below